Independent Thesis Project

Weitzman School of Design, University of Pennsylvania

2021-2023

Advisor: Architect Philip Ryan, AIA, Adjunct Professor

Disassembling by Design is the result of a year-long interdisciplinary research in the fields of architecture, construction, preservation, and rehabilitation. The work developed for this book hopes to become a reference for a design approach that embraces the challenges of our earth, our natural resources, and the importance of locally sourcing our built environment. This thesis helped envision alternative procedures for the decaying, but beautiful and materially rich structures that stand abandoned and often overlooked in many communities in Puerto Rico and around the world. The book compiles literature, analysis and visuals showcasing relevant concepts such as post-destruction design, maintenance and repair in architecture, the life and death of buildings, the obsolescence economy, the concept of circular design, and vernacular construction, etc.

This project started as an urge to examine our current architecture, construction, and demolition practices in relation to depleting material supply chains and as a critique to cultures of endless disposal. As the research evolved, the project became more about understanding the taxonomy behind reclaimed materials of a given site and looking into the implications of reassembling them back to newer and more attuned services for the future building users. I am a designer trained in architecture and urban planning, so Disassembling by Design was an opportunity for integrating both the aesthetics of what I called “slow build” and its potential socio-economic effects in the long term.

Special acknowledgements to professor Philip Ryan for his guidance and intellectual support in the process, to Laia Mogas for being a fundamental critique in framing my research scope, to Hector J. Berdecía for his assistance in outreaching to local archives back in Puerto Rico, and to preservation architect Orlando de la Rosa for sharing his incredible insight and experience on the history of industrial patrimony in Puerto Rico. I want to also thank local engineer Kevin Rivera and agronomist Hector T. Martí for helping me tour the site twice and collect over 800 photographs of the place. Other contributors that were foundational for the first half of the research were Revolution Recovery, a material and construction debris recycling facility in Philadelphia, and the Provenance Salvage warehouse, who offered interviews on the topic of demolition waste recycling and management.

This thesis project is based on the argument that waste generated from building construction and demolition can become a valuable source for rehabilitation design. Mainly, it explores methods in which architectural design can contribute to more locally sourced design and construction processes, using carefully examined materials, components, and assemblages in situ as instruments for reconceiving how we rehabilitate and occupy space in the context of climate change and resource scarcity. Accordingly, architects cannot claim to be doing sustainable architecture in a conceptual realm while designing buildings that are programmed to be demolished and become waste in timelines that are shorter than their actual performance and durability. Furthermore, the idea that architecture will always be built from raw and “newly” fabricated materials is obsolete and unsustainable in today’s environmentally deprived context. This argument is important for several areas within architecture like those related to adaptive reuse, sustainable construction, building retrofitting, environmental sustainability, and building management.

Four guiding questions formulated the research scope and the objectives of the thesis. They emphasize the challenges behind performing a building’s taxonomy and understanding circular construction in a world that mainly operates within a linear metabolism logic:

• What design assemblages and aesthetics can thrive from upcycled and reclaimed materials found in existing building stock?

• When should the processes of deconstruction and disassembling become a present tool for new design and construction techniques?

• How can we determine reusability potential driven by qualitative values and not solely by economic and technical feasibility in a global scale?

• How can circular design thinking positively serve rehabilitation of industrial heritage sites and unfold cultural values in the context of island construction?

• When should the processes of deconstruction and disassembling become a present tool for new design and construction techniques?

• How can we determine reusability potential driven by qualitative values and not solely by economic and technical feasibility in a global scale?

• How can circular design thinking positively serve rehabilitation of industrial heritage sites and unfold cultural values in the context of island construction?

Part I - The Research

The first part of this thesis is a look into the social-economic aspects of how we currently do architecture and the consequences of generating endless waste from construction and demolition practices. Several authors have studied construction systems and alternative models of doing buildings through the concepts of circular economy, cradle-to-cradle thinking and deconstruction.

To deal with waste of any kind, one must ask where does the idea of “waste” originates from. All metabolic systems in the universe operate in a circular life cycle, then were does the linearity of our modern production systems becomes parallel to that metabolic nature? Like Heather Roger’s Gone Tomorrow book affirms the first step into changing wasteful architecture processes is reduction, meaning a massive discontinuation of objects designed for obsolescence. Reducing it in volume and then develop a radical reuse plan for manufacturing buildings able to extend their material’s service life.

The following mind map diagram summarizes everything that was documented throughout the research phase of the thesis. Basically, all the elements related to circular design; building deconstruction and disassembly; construction and demolition waste and recycling. The observation drawn from this is that, in a practical application, the majority of efforts concerning disassembly and reuse are concentrated within the realms of maintenance, repair, and facility management, rather than being integrated into the initial design stages. This stems from the perception that, in theory, material reuse and deconstruction processes are often viewed as economic considerations rather than design focal points. It’s worth noting that the thesis makes emphasis on the concepts highlighted in red. This includes urban mining to account for materials within a specific site; the concept of “building in place” as a conduit for circular design, involving innovative exploration of material reservoirs; deconstruction as a guiding methodology for dismantling structures into components; and lastly, rehabilitation as an opportunity to reinvigorate underutilized structures with significant potential.

Part II - The Design Methodology

The research provided a methodical understanding of the concepts of "Construction and Demolition Waste (CDW) and "Design for Disassembly" (DfD), forming the foundation for the design methodology. This involved integrating the concepts of CDW and DfD, with the specific intent of the site.

The primary objective was to comprehensively analyze existing recycling or reusing options. By moving away from the linear metabolism that we previously examined, materials within the facility were subject to an urban mining process and evaluated based on their potential for reuse. This led to the development of material and element inventories, as well as the formulation of dismantling and reuse strategies with which a design proposal could develop.

Following that examination, an assessment and selection of specific materials and parts was conducted to determine the optimal reuse options. Concrete spatial interventions, considering both the re-installation of salvaged pieces and the integration of ephemeral and newer permanent solutions, were developed for the design rehabilitation of the refinery. The aim was to create a design that started as a temporal intervention, carefully integrating more enduring and permanent elements based on experience and long-term use and adaptation.

The primary objective was to comprehensively analyze existing recycling or reusing options. By moving away from the linear metabolism that we previously examined, materials within the facility were subject to an urban mining process and evaluated based on their potential for reuse. This led to the development of material and element inventories, as well as the formulation of dismantling and reuse strategies with which a design proposal could develop.

Following that examination, an assessment and selection of specific materials and parts was conducted to determine the optimal reuse options. Concrete spatial interventions, considering both the re-installation of salvaged pieces and the integration of ephemeral and newer permanent solutions, were developed for the design rehabilitation of the refinery. The aim was to create a design that started as a temporal intervention, carefully integrating more enduring and permanent elements based on experience and long-term use and adaptation.

The design methodology is driven by these seven phases:

• Understand material flows and current recycling options

• Inventory of materials and buiding elements

• Visualize material reuse and disassembly strategies

• Inventory of assemblies

• Best options for reuse (BOR) assesment

• Programmatic profiles for new use based on BOR

• Deploying strategy for reassembly and prototype on site

Material Stock and Flows Diagram, adapted from M. Arora et. al., 2020.

Material Flows and Current Recycling Systems

Urban mining is the process of reusing building materials reclaimed from a demolition or an existing structure. Designers have the potential to expand the reuse possibilities of these elements by categorizing and rethinking configurations for them. The diagram below visualizes how designers can start defining a process for reclaiming these materials. Similar ideas have been researched through lifeycle assesments (LCA), for example.

Five Steps

The research helped define five specific steps for design that would prototype how architectural thinking could operate within a circular metabolism in a specific context, the Coloso Refinery in Aguada, Puerto Rico.

• Step 1: Material Mining - A spatial analysis of materials available in the built environment to identify “mining” potential in existing manufactured assets. According to scholars, investors and researchers, cities are stockpiles for the circular economy as they cover 2% of the Earth’s surface but consume around 75% of its resources. “Today, every medium-sized European city contains more copper than an average copper mine.” (Kohl, 2019)

• Step 2: Shearing Layers of Change - In dismantling a building, we need to understand that they are comprised of mutliple elements that change at different speed rates. Its constituents tear apart at different points in time. Steward Brand has been someone looking into this through the concept of the Six S’ where he explains buildings through six layers of change: site, structure, skin, services, space plan, and stuff. As we aim to deconstruct buildings, we need to understand its component’s behavior and the implications of reusing it.

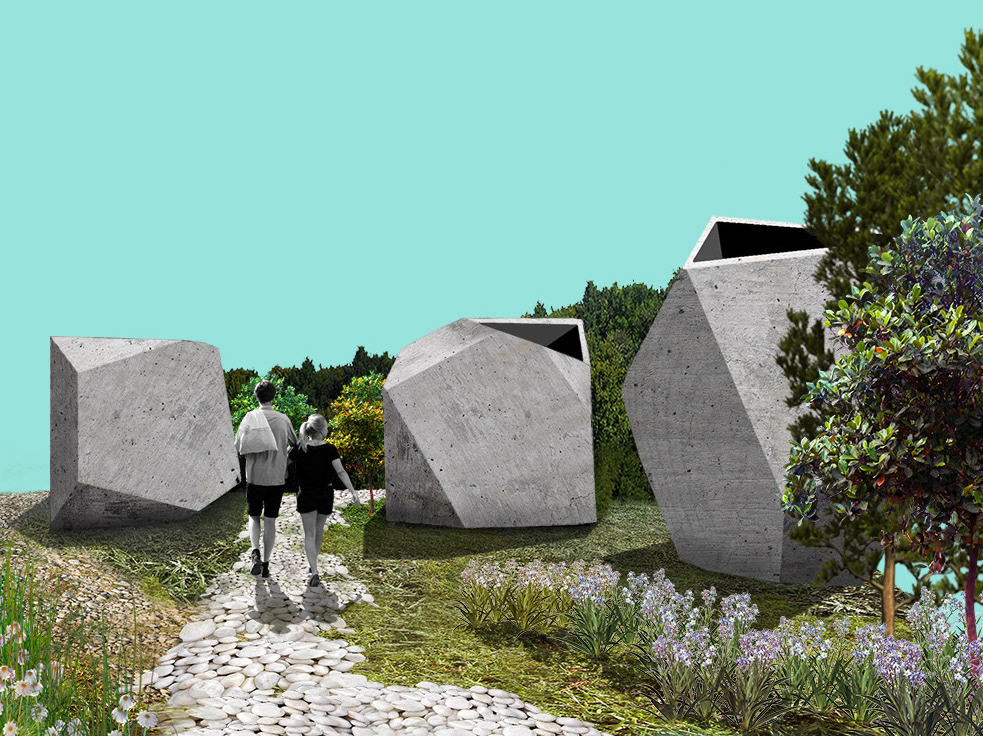

• Step 3: Deconstruction / Disassembling - Breaking things back into pieces, looking at the deconstruction and the process of construction in reverse. This leads to Jackson’s concept of rethinking repair and broken world thinking (2014). Case studies for this are Edward Burtynsky’s Ship Breaking phorographs in Bangladesh, and Tod McLellan series “Things Come Apart”.

• Step 4: “Slow Build” / Building in Place - Slow build questions the traditional building process. Financially and materially this would mean a construction process that is need-based, not feasiblity or price-time based.

• Step 5: Rethinking Repair - Incorporating the notion of repair from the get-go, which in this case parts from an existing set of fixed elements that may not comply with contemporary construction standards.

Coloso Refinery, Aerial view of the valley, 2020

An Incremental Program

A disassembling-by-design program operates incrementally, aligning with the notion of gradual construction and repair. Building construction and use must not be viewed as singular interventions; rather, they should delve into the intrinsic programmatic values that emerge over time from on-site materials, the repair and reuse process, and the user experience. Lina Bo Bardi’s adaptive reuse approach in SESC Pompeia serves as a case study. Here, architectural strategies forge a fresh identity for the factory spaces, preserving old details alongside new elements. In the context of Coloso, a similar transformation would blend reclaimed materials with new additions via a circular design approach, creating a hybrid that melds contemporary needs with the building’s historical value. Any new material incorporated into this process aims to fortify the existing

stock, spatially and tectonically. Sugar refineries are a big heritage piece of Puerto Rico’s socio-economic development, however it is important to find a threshold between the historical significance of those monumental structures, and the more contemporary models of sustainable construction and rehabilitation. This thesis imagined a scenario buffered program for Coloso, broken in phases of repair, rehabilitation, and multiple uses over time

stock, spatially and tectonically. Sugar refineries are a big heritage piece of Puerto Rico’s socio-economic development, however it is important to find a threshold between the historical significance of those monumental structures, and the more contemporary models of sustainable construction and rehabilitation. This thesis imagined a scenario buffered program for Coloso, broken in phases of repair, rehabilitation, and multiple uses over time

Diagram adapted from Steward Brand’s How Buildings Learn. (1994)

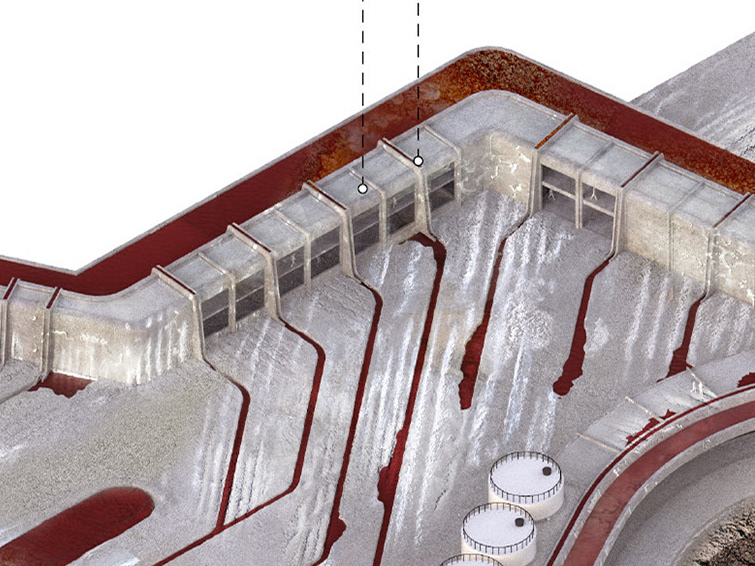

Approach to Site

On site, the design methodology and scenario buffered strategy manifests in the 4 stages diagrammed here. Firstly, there’s the observation and surveying of the buildings, which involves establishing a framework for why, what, and how to preserve them. The second stage centers around material harvesting. This entails cleansing the building from its current state while documenting deconstruction schedules and categorizing material and fixture types. The third stage encompasses designing strategies for rehabilitation and reinstallation. Lastly, the fourth stage involves simulating and conceptualizing the building’s future across scenarios of repair, ecological vitality, and decomposition. This essentially offers a glimpse into potential processes such as recycling the building anew or allowing it to naturally integrate into the landscape as part of its lifecycle.

For Puerto Ricans, it is evident that present-day needs go beyond sugar production, we are no longer that type of colony. The territory has become more aware of the relevance in creating diverse economic growth from the ground, self-organizing models of production, and protecting ecological resources and their preservation for future generations. To think that a circular model like the one studied in this thesis would be too far out of reach in the island’s socio-political context is to assume and perpetuate that dependency mindset that we are aware has sabotaged Puerto Rico’s economic autonomy for over a century.

For Puerto Ricans, it is evident that present-day needs go beyond sugar production, we are no longer that type of colony. The territory has become more aware of the relevance in creating diverse economic growth from the ground, self-organizing models of production, and protecting ecological resources and their preservation for future generations. To think that a circular model like the one studied in this thesis would be too far out of reach in the island’s socio-political context is to assume and perpetuate that dependency mindset that we are aware has sabotaged Puerto Rico’s economic autonomy for over a century.

The Final Case Study:

Rehabilitation, Repair and Maintenance of Industrial Heritage in Island Construction Systems

Central Coloso was the fourth largest locally owned sugar refinery in the western part of Puerto Rico. It was the last refinery to cease operations in the island in 2003, since then it has joined the robust network of industrial ruins with a monumental cultural presence in the island. Refineries in Puerto Rico trace back in history to the 16th century. They are a peak-oil-era heritage recording the colonial extraction models of capitalization in the Caribbean.

As extractive as they were, they imported high levels of technologies, infrastructure, materials, and assets into the island. Economically, they represent centralization of capital and corporate finance. We’re talking about an island wide network of agro-industrial infrastructure that was interconnected by a highly advanced railway system along the coast as you can see on the map.9 Because these complexes only served the extraction agenda and absentee enterprise model from the United States, it became an incomplete and discontinued ruin throughout the island once the business was “over”. Today, the Puerto Rico Land Authority (ADT) owns all the refinery buildings and rents some of their lands for agricultural purposes. Not bigger vision or future plan is depicted for these monuments, and the clock is ticking as we see them being sold, demolished or deteriorated day by day.

As extractive as they were, they imported high levels of technologies, infrastructure, materials, and assets into the island. Economically, they represent centralization of capital and corporate finance. We’re talking about an island wide network of agro-industrial infrastructure that was interconnected by a highly advanced railway system along the coast as you can see on the map.9 Because these complexes only served the extraction agenda and absentee enterprise model from the United States, it became an incomplete and discontinued ruin throughout the island once the business was “over”. Today, the Puerto Rico Land Authority (ADT) owns all the refinery buildings and rents some of their lands for agricultural purposes. Not bigger vision or future plan is depicted for these monuments, and the clock is ticking as we see them being sold, demolished or deteriorated day by day.